Book Review

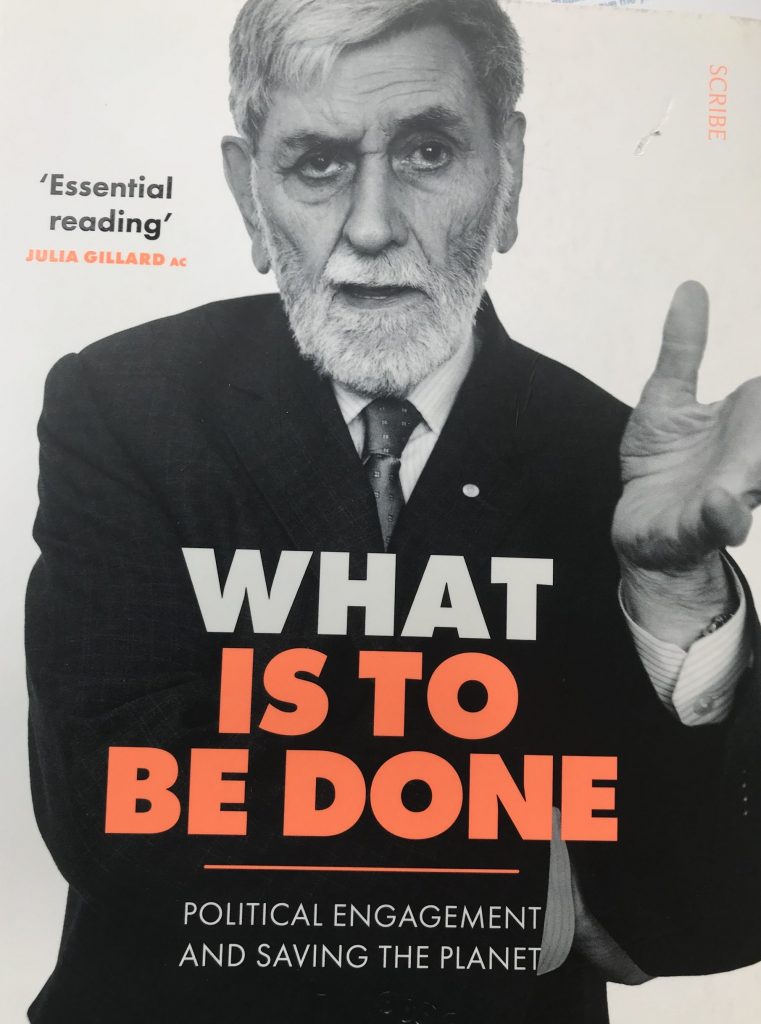

Barry Jones

Scribe Rrp $35.00

In his preface, Jones lists “the four horsemen of the apocalypse that threaten humanity: . . . population growth exacerbated by per capita resource use; climate change; pandemics; and racism and state violence.” The lead horse is population, which pandemics might reign in. The latter two horses are mostly irrelevant to saving the biosphere, but do allow Jones to expound on some of his favourite themes.

The first chapter discusses his Sleeper’s, Wake!, whichexplored the impacts of a post-industrial, information revolution and how we should prepare and position ourselves during this upheaval. Jones looks back on the first publication of Sleeper’s, Wake! when he was a shadow Labor Minister for the Federal House of Representatives, on the threshold of becoming Australia’s longest-serving Minister for Science (1983-1990) with the election of Bob Hawke as PM.

“Political colleagues saw me as too individual and idiosyncratic (that is ‘weird’), not a team player, and totally lacking in the killer instinct, while many in the academic community might have seen me as too political, even too populist.” After 26 years in Victorian state and federal politics, Barry “…left politics with a profound sense of frustration and unease…In politics, my timing was appalling. I kept raising issues long before their significance was widely recognised. That made me, not a prophet, but an isolated nerd. I can claim to have put six issues on the national agenda, but started talking about them ten, fifteen, or twenty years before any of my political colleagues were ready to listen.”

There is some pique as he reviews his exclusion and marginalisation in what is a classic example of Tall Poppy Syndrome. Although Jones “greatly admired Hawke’s skills…this admiration was not reciprocated. Indeed he (Hawke) found me profoundly irritating. The attention generated by Sleeper’s, Wake! was a major factor in this.”

Jones’ use of the terms ‘post-industrial’ and ‘sunrise industries’ upset a lot in his party. Sleeper’s, Wake! “probably had more influence overseas than in Australia…translated into Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Swedish – and Braille.” Jones was interviewed by David Frost and Michael Parkinson (BBC) and his book featured in New Scientist, New Statesman, the Christian Science Monitor, Playboy, and Nature, “the world’s most important scientific journal”.

Bill Gates had read Sleepers, and visited Jones in Canberra in 1984: “Bob Hawke and Paul Keating were too busy to fit him in.” A report from the OECD (1985) endorsed Jones’ views “but was very critical of a submission from the Department of Finance. Finance took this very badly, and thereafter I became a target when future budgets were being prepared.”

New Industries

The reduction of Australia’s tariffs, opening the Australian economy to global competition, was initiated by Hawke and Keating, resulting in the loss and translocation of most of Australia’s manufacturing. Jones advocated support for the creation of new industries. The response: “This is exactly the same as the special pleading by the manufacturers of shirts and motor vehicles. If we subsidise new industries, we’ll have to maintain support for old ones. Leave it to the markets to decide where to allocate resources.”

Jones was the only Australian Minister to address the G-7, which he did near Ottawa in October, 1985, taking leave and paying his own economy air fare, after Hawke “smartly refused” his request for approval. “My accompanying officials travelled first class, because I could authorise their travel but not my own.”

Jones’ invitations to visit the Asia Society in New York and the New England-Australian Business Council in Boston (December, 1985), Seoul (1987), Sudbury, Ontario were refused funding. Jones chaired the OECD examiner’s review of the Yugoslav economy (1987). Hawke was touring Europe at the same time and was scheduled to meet the Yugoslav Prime Minister, Mikulic, and when told the meeting had to be shortened because Mikulic was meeting with Barry Jones, Hawke responded “Barry fucking Jones? Here in

Dubrovnik?” In 1990, Jones was invited to participate in an international think tank, advising Gorbachev on Perestroika, but was refused. “However”, Jones recalls, “my friend Emanuel Klein was able to get funding from Sir Peter Abeles, an intimate of Hawke.”

Jones first became aware of anthropogenic Climate Change in 1967, after interviewing Lord Ritchie Calder, a Scottish science writer, on talkback commercial radio program in Melbourne. Jones was one of the first Australian politicians to take up the issue in 1984. Jones often resorts to “begging the question” in his writing: “Climate change is the great moral challenge for this generation, with profound implications about how we make choices. Short term or long term? Consumption or preservation? Ourselves or our descendants? Rejecting or examining evidence and expertise? Emotion or rationality in making political choices?”

He links Climate Change to a range of issues, including political paralysis, “loss of faith in our institutions and the Western liberal tradition, …rise of authoritarian governments, snarling nationalism, and, often, irrational leaders.”

Digital Revolution

Jones mentions Marshal McLuhan and his acolyte Neil Postman, so would be aware of the fundamental impacts from the shift from print to the electronic culture (epitomised by its contrived superficial images with embedded subliminal memes) but, nonetheless, rails against these impacts: “The digital revolution, contrary to what might have been expected, has played a central role in the dumbing-down political discourse and narrowing many people’s understanding of the world and its problems.” He discusses “confirmation bias” where people search the web for material which reinforces their preconceptions and prejudices. He mentions our Julian Assange and the “growing imbalance between the information collected about citizens without their knowledge and arbitrary restrictions on what citizens were allowed to know…Democratic practice rests on the premise that citizens know what they are voting about and who they are voting for. If such information is denied, or massaged to conceal the reality, can we still call our nation a democracy?” Jones concludes the debate between what is often invoked as national security, genuine national security, and the public’s right to know, remains unresolved.

“The digital revolution has…become an instrument for nativist populism, conspiracy theories, the cherry-picking of evidence, and the trashing of expertise.” Although Jones states “The digital revolution has transformed our lives, mostly for the good (italics mine), and we cannot retreat from it…the outreach of misinformation has increased exponentially. And Donald Trump can be regarded as its end product – so far.”

Trump

Jones’ Chapter Five is titled “The Trump Phenomenon” and discusses him in considerable detail. Jones refers to a 2012 University of Chicago survey which revealed only 74% of Americans knew whether the earth circled the sun or the sun circled the earth. 18% of Americans reject evolution, 48 percent think evolution was directed by God, with 33% accepting Darwin’s theory. This stupidity is contrasted with the fact that Americans “have won or shared more Nobel Prizes (383) than any other nation, by far.” Jones quotes Putin stating “Western democratic values such as multiculturalism and social tolerance were no longer accepted by most people” and that “Western-style liberalism was obsolete.” When Trump was asked to respond, “He thought Putin was talking about California, and then engaged in a diatribe during which he agreed with Putin’s non-existent criticism of city administrations by liberals in San Francisco and Los Angeles.” However, Jones may also have missed the central point: Putin may be correct. Multi-culturalism and high levels of immigration haven’t been presented as election issues by the major parties and thus may not be “democratic values”, but socio-political ones, determined by political elites.

Jones attributes a range of issues to Climate Change, including “polluted river systems; a decline in fish stocks; the disappearance of bees and butterflies in many areas; reductions in the numbers of birds; and hazardous air quality in many cities.” However, most of these are multi-factorial and some are, thus far, quite independent of Climate Change. Trump-like, Jones repeats this fabrication: “Climate change is a major factor in the destruction of habitat and species loss, especially bees, birds, and insects, with their major impact on agriculture.”

The major factors are land-clearance for agriculture (with its attendant use of pesticides and fertilisers) and urban expansion, both inter-connected with population increase.

Jones, in his Chapter Six, “Climate Change: the science”, includes a graph of the concentration of C02 during ice ages and warm periods for the past 800,000 years, showing a relationship between CO2 and warmth. The causality is complicated: Did a lowering of CO2 trigger ice ages, or did the retreat of forests and the extension of sea ice, thereby inhibiting photosynthetic activity, lower CO2 levels?

Jones discusses The Little Ice Age (1300-1870, peaking at 1650): “It has been attributed to several factors: decreased solar radiation; changes in ocean circulation; the degree of glaciation; massive volcanic eruptions after 1257; and falls in population due to the Black Death and colonial slaughter in the Americas.” However, the depopulation of the Amazon (and subsequent resurgence of rainforest) resulted more from introduced Eurasian disease epidemics like smallpox, than “colonial slaughter”. Depopulating global tropical rainforest zones would cool the planet.

In Chapter 7, “Climate Change: the politics”, under the heading “How good is Australia?”, Jones begs 15 questions which he believes should be posed to “Ministers, and especially the Prime Minister…” Question 8: “Why does Australia produce three times more carbon dioxide emissions per capita than the United Kingdom and twice as much as New Zealand? Is their quality of life so inferior to ours?”

The answer may be one of geography, related to Australia’s much greater size, its vast dry interior concentrating population around a 25,760 km perimeter with large transport distances. Jones does discuss the considerable release of CO2 from the manufacture of concrete for construction and infrastructure, driven, in turn, by the high levels of immigration.

Writing Style

Jones has adopted a polemical style of writing, consigning the 2019-20 bushfire season to Climate Change, although it would be more accurate to say the calamity was worsened by Climate Change. Australians commonly reside in areas of great danger, building their homes within pyrophyllic Eucalypts, among the most flammable forests on the globe. Urban expansion from “tree changers”, has resulted in even more Australians living in high fire-risk areas, in turn, increasing further deforestation for public safety post-fire.

Jones can be tiresomely partisan, sometimes churlish and snarky from all his years in the bearpit. A tripartite classification system of politicians was proposed by Labour British politician, Tony Benn: 1.) mad person who breaks rules and reaches for the sky, 2.) the straight person, transparent, persistent, predictable and well organised; and 3.) the fixer, versatile, opportunistic and mercurial.

Jones states “I happily include myself in the ‘mad’ category, because I was always aiming for objectives that were seen as beyond the reach of conventional politics, although I was strikingly deficient in the killer instinct.” Oddly, Jones places Trump, Boris Johnson, and Margaret Thatcher alongside Gough Whitlam, Paul Keating, and Kevin Rudd in his group of Mad Apes.

“Scott Morrison”, Jones declares, “has a weird idea that the future is simply a linear projection of the past, so that if your father was a coal miner or policeman, that’s what you will be-and your sons, too. In his vision, if you want to communicate but are away from home, you look for a public telephone or post a letter. If you want some money, you cash a cheque. It’s not back to the 1980s, more like the 1950s.” This is low-level Parliamentary discourse; it does nobody any good, least of all his cause.

Ironically, Jones appears to subscribe to a linear progress concept of history where Homo sapiens has been continuously progressing (towards what?). A completely different view is the cyclical theory of human history proposed by Oswald Spengler (The Decline of the West, published 1918), which, his contemporary, German sinologist Richard Wilhelm,

Cycles

revealed in his translations of ancient Chinese texts like the I Ching (stretching back to the 9th century BC) was a long-established historical and social perspective in China. In a cyclical framework, cultures and empires metaphorically, resemble organisms, having a birth, youth, maturity, senescence and death, with new cultures arising from their ashes like the phoenix. If so, where are we now in what cycle? A cyclical framework might explain Jones’ many frustrations and negative observations, in spite of which, he struggles for optimism: “Despite all this, we have to be optimistic that we will have the wisdom, courage, and skill to save the planet—and ourselves. It’s the only way to go.” We should also have to be realistic and pragmatic.

Jones probes Climate-change sceptics: “They simply deny that global warming is occurring, asserting (again, without evidence) the case that the atmosphere is cooling and that scientists involved in the IPCC are engaged in self-promoting fraud, while lobbyists for the fossil-fuel industry operate only from the purest motives.” I suspect this relates back to the breakdown in trust in our government and institutions and a cynicism that everyone is acting out of self-interest.

In Chapter 8, “Retail Politics: targeted, toxic, trivial, and disengaged”, Jones divides Australia’s “hegemonic parties”: “I lump the Liberals and Nationals together, in practice, despite their often-significant differences on ideology, personalities, and entitlements to the spoils of office. They emphasise individual effort and rewards, but are eager to offer collective help such as fuel and water subsidies…Labor, historically, has emphasised the collective, as with Medicare and compulsory superannuation. Both hegemonic parties have become ‘shelf companies’, with small, ageing memberships, large numbers of ‘stacks’, and are oligarchic, not democratic, in practice. Party activists are, in effect, traders, apparatchiks, and future lobbyists. They are characterised by personality cults, factions, and ethnic recruitment.” He might have also discussed the revolving door between industry and politicians and bureaucrats. Our own Mark Vaile now chairs Whitehaven Coal.

Jones goes on to comment on the U.S. and “Nixon’s silent majority” with 6 prejudicial dot points, then transfers this blighted strategy to John Howard, who, although a fellow “living treasure”, he describes as a “dog-whistling virtuoso who enthusiastically adopted the Nixon strategy.” Jones goes on to critique conservative prime ministers rather more harshly than Labor ones. “After 1996, racism became once more an important issue in Australian politics.” Did I hear a whistle there from Jones?

White Australia

Jones continues with his polarisation, trivialisation and bias: “In Australia, opposition to ‘political correctness’ is coded language for the support of White Australia, settler values, Australia Day, and the Australian flag; the celebration of Gallipoli and the monarchy; and uneasiness about multiculturalism…I suspect that many Liberal voters feel uneasy about discussing politics, whereas Labor voters can’t help themselves…My father (not a Labor voter) used to say that Liberal voters could be identified because they always shined their shoes.”

In his discussion of political disengagement, Jones writes about the decline of party membership which he estimates is now at .2 per cent of the population, compared with 4 per cent in Menzies’ Liberal party in 1950. He cites Cathy Alexander (Crikey, 18 July 2013): ‘There are more people on the waiting list to join the Melbourne Cricket Club than there are rank-and-file members in all Australian political parties put together.’ The MCC figure was 232,000.”

Jones observes “In practice, an active and strategically placed minority can exercise far more power than a large and uncoordinated majority” which gives some credence to the concept of silent and quiet majorities with simmering resentments.

Still Clings to Bipartisanship

Jones, at 88, stubbornly clings to his bipartisanship, whatever the contrary evidence: “Oddly, despite the white racist elements in the Conservatives (British), it has 22 MP’s, and some peers, of Asian or African descent, including two successive chancellors (Sajid Javid and Rishi Sunuk).” In his discussion of Boris Johnson and Brexit, Jones observes the “British Labour Party has a membership of 580,000…The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds has 1.1 million members—more than all Britain’s major political parties combined.” A laudable expression of priorities from the British.

Jones discusses the increasingly toxic political life in Canberra, which he ascribes to trivialisation, an avoidance of serious debate, and “only two preoccupations: personal career advancement and winning the next election.” He cites Rudd’s appointment of former LNP politicians as justices and ambassadors as examples of being fairer than Morrison’s appointment of ALP Gary Gray as Ambassador to Ireland, which he describes as a “rarity”. Both PM’s choices may have been influenced by the available candidates at the particular time.

Jones links the Black Lives Matter movement with the Aboriginal Deaths in Custody and then, drawing on an even longer bow, to the destruction of the rock shelters by Rio Tinto, as “Black Heritage Matters”. Unfortunately, “Implausible though it sounds, the relevant federal and state ministers were both Indigenous, related – as uncle and nephew—from different political parties, ill-informed and ineffectual”.

Although Jones insists “Most of all, we need a higher level of citizen involvement in the whole process of public debate, instead of leaving it all to the political professionals.”

How is this going to happen? Politics is so filled with narcissists, opportunists and sociopaths (the terms are not mutually exclusive), decent people necessarily shun it in order to preserve their decency. There was never a referendum for multi-culturalism or immigration levels, or what a sustainable population for Australia might be. Although Professor Blainey attempted to raise these issues, hysterical accusations of racism and xenophobia were dog-whistled aborting a fundamental concern which should have already been publicly debated. Blainey’s Triumph of the Nomads (1975)stands as an unparalleled poetical/historical masterpiece championing Australia’s phenomenal pre-European history.

Dr John Stockard OAM

Wingham, NSW

(Second part of this review will be in the January edition of the Manning Community News.)