Robert Milliken reviews a lively new history of the car ferries that once made crossing Wallis Lake an adventure.

Traversing rivers and lakes on the mid-north coast once involved driving cars on to punts, and crossing your fingers that you reached the other side. No such journey was more colourful, dramatic and dangerous than the one over Wallis Lake between Tuncurry and Forster.

Punts that plied the Manning River at Wingham and Tinonee were placid by comparison. Such coastal river punts were usually attached to wire ropes strung between river banks. This allowed the ferryman on the punt, or a launch beside it, to guide them across quite easily.

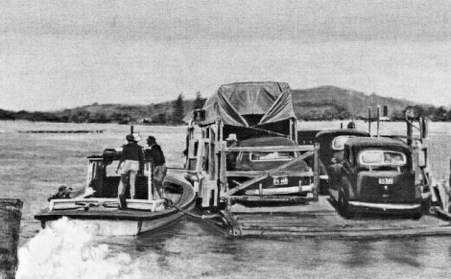

No such arrangement was possible on Wallis Lake. Passengers’ fates were left to the skills of the ferrymen, who had to steer the punts through swirling tides, ever-changing sandbars and fast-flowing waters at the mouth of the Wallamba River, often at night. One punt sank, and at least one was almost swept out to sea. Overloading was commonplace: several vehicles fell off the ends of punts and plunged into deep water. Miraculously, no lives were ever lost.

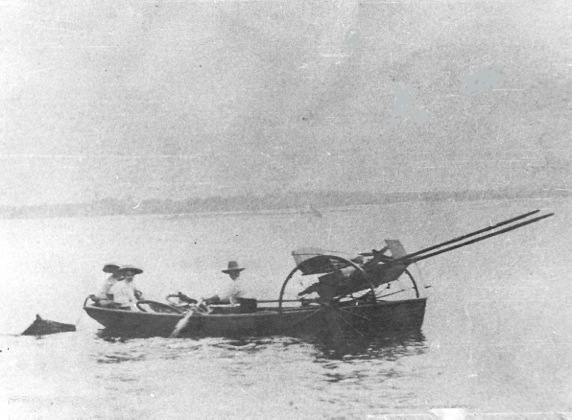

Chris Borough has now written a fascinating history of this adventurous era, Connecting Forster and Tuncurry – the Unique Forster Ferry Service, for the Great Lakes Historical Co-Operative Society. It starts in 1890 when John Kennewell introduced the first passenger service between Minimbah, the Aboriginal name for Forster, and Tuncurry, the Aboriginal name for what was once known as North Forster. Kennewell’s operation was just a rowing boat: passengers straddled their sulkies across the front of it, while their horses swam behind.

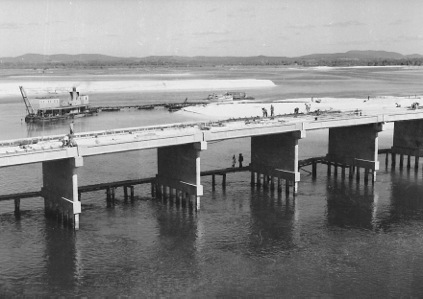

The bridge that now exists, finally opened in 1959, after years of lobbying by exasperated locals, and indifference by bureaucracy’s mandarins in Sydney. One of the most enterprising figures across this 69-year saga was Charles (Charlie) Blows, who had started a ferry for walk-on passengers in 1921. Blows successfully lobbied the then Manning Shire Council, whose remit extended to Wallis Lake, and introduced the first vehicle ferry in 1924. It held just one car.

As the number of holidaymakers grew, Blows’ punt quickly became obsolete. So, three years later, he offered to build a four-car punt, at no cost to the council, in return for an extension of his lease to operate the service. The council agreed to this win-win deal, but the Minister for Local Government in Sydney, for some inexplicable reason, refused it.

This was but one of several bureaucratic debacles in which authorities seemed set on stifling a more efficient service. In 1928, Forster was transferred to the Stroud Shire, leaving Tuncurry in the Manning Shire and Wallis Lake, in an apparent no-man’s land. Inevitably, bickering broke out between the two councils over which one was to control and pay for the ferry service. A compromise of sorts was reached in 1933. After the Minister had rejected Blows’ offer to build a bigger punt, Manning Shire offered to supply one that had worked the Manning River at Wingham for about 20 years. It was capable of holding two large cars or three small ones.

My personal experience with the Wallis Lake punt happened as a child in the early 1950s. My parents, David and Thelma Milliken, then owned the Wingham Hotel. Our family drove to Forster just after Christmas each year to join several of our Wingham friends for summer holidays. There had been several ferrymen, and at least two more punts, since Charlie Blows started the service in 1924. By now, Blows was operating it once again, this time with his two sons, Colin and Warren.

But the punt’s capacity had barely changed in decades. It was only from reading Borough’s history that I learned the punt we travelled on in the 1950s was the same four-car vessel that had started operating on Christmas Eve in 1938. But in these prosperous post-war years, demand for the punt had exploded. Six cars were usually crammed on to it, those at each end perched dangerously on the punt’s flaps lapping the water.

The drive from Wingham to Tuncurry took a fraction of the time it then took to get a berth on the punt. As my sister Sue Milliken recalled 11 years ago in a Sydney Morning Herald article (quoted in Borough’s history), “the queue to get on to this inefficient and unpredictable water transport could be dozens of cars long, stretching back up the road, past the Wrights’ sawmill, almost to the shops.”

Finally, getting on board was often not the end of it: “The most common occurrence was getting stuck on a sandbar. There would be a revving of the boat engine, a grinding, a swirling of sand clouding the shallow water, a shuddering, and a stop. This was followed by groans from the passengers, who knew this could mean anything from one to three or more hours waiting either for the spare boat to be brought over to help pull the punt off, or for the tide to rise.”

It was fun for us kids, but for the adults, the bridge could not come soon enough. Festooned with flags, the Blows’ punt unloaded cars for the last time on July 18, 1959. And with the bridge’s one lane capacity each way unchanged in the 57 years since then, the holiday car queues have long returned.

The ferry’s turbulent history provided rich reporting material for newspapers, stretching from Sydney and Maitland to Taree and Dungog for 70 years from the 1890s. It was an era when newspapers were the prime sources of public information. Borough has drawn meticulously on these accounts, and enlivened his narrative with pictures from the Great Lakes Museum and other sources. He acknowledges the advent of the Internet and the National Library of Australia’s digitised newspaper collection, Trove, for making his accurate history possible. With federal government funding cuts now threatening Trove’s future, Borough’s history is a prime exhibit in the case for saving this national treasure.

Connecting Forster and Tuncurry – the Unique Forster Ferry Service, is available for $20 (plus postage) from the Great Lakes Historical Co-Operative Society, at the Great Lakes Museum, 1 Capel Street, Tuncurry NSW 2428.

Photos courtesy Great Lakes Museum.