By Jane Connors.

Published by the National Library of Australia

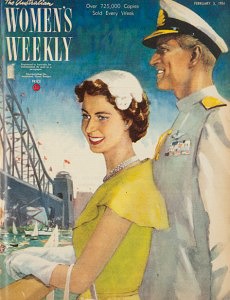

On Wednesday, April 3, l954 “at precisely 10.33 am, a small foot in a white peep toed sandal came slowly down upon a pontoon to Farm Cove,” and the ABC broadcast to the country that “The Queen is now in Australia.” Her Majesty was young, sweet, gracious, and the first reigning monarch to visit. She wore a pretty yellow dress, white hat, gloves and handbag – and beside her, the impossibly tall, blond and handsome Prince Phillip.

The streets and harbour foreshores were clogged with people, their lunches wrapped in wax paper, and, it’s said, maps of where the lavatories could be found. In the following weeks, in a population of nine million, its estimated seven million set out to see her.

By the end of the first day in Sydney more than 2000 people had succumbed to the crowds and the excitement, and 60 went to hospital, including a soldier who collapsed on his own bayonet and “knocked out a couple of teeth.”

This is a big, fine book with a very serious historical purpose, with lots of photos and illustrations, and a light, witty touch.

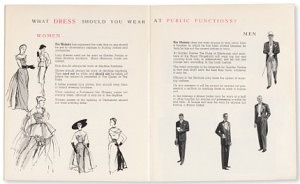

The preparations for this royal visit had been extraordinary, right down to how many buttons were appropriate on ladies’ gloves worn to evening receptions.

Greeted with Exuberance

Every visit since 1867 when Prince Alfred came, every Royal, no matter how minor, saw an exuberance of tickertape, banners, arches, all manner of festoonery, red carpets, flowers and fireworks, furry animals of every kind, and miles and miles of dignitaries and VIPs lined up to shake the royal glove or at least get a glimpse. There were endless garden parties, sometimes in sweltering heat. There were hundreds of speeches – and parades. One lovely picture in the book shows Queen Elizabeth again in her peep-toed shoes walking past a Guard of Honour of the finest wool sheep in the country, all displaying their precious rumps as she walked past.

There’s a nice story about mistaken identity. People in the northern beaches lined the streets as the big black cars headed up the peninsula. But it wasn’t her Royal Highness going out to Pittwater, just the Ladies in Waiting. Apparently Lady Mountbatten changed into a swimming costume and was reported to have been waterskiing for nearly an hour.

Everywhere Her Majesty went, amid the adulation and cheering, not everyone was enthralled. Here’s one quote from The Bulletin at the time, when a Labour member for Gellibrand wrote he was hoping to be spared the “prancing politicians, shire bumbles and heavyweights, ponderous, boring people and brass hats to drive the Queen and her entourage into the ground and weary them with inanities and reiterations.”

There were some serious incidents, quickly hushed up. It seems someone put a log on the train line when the Royals were going over the Blue Mountains. Fortunately it fell off. The log, not the train.

Threatened Plots

The Catholic Irish were a constant fear in a society ruled by English Protestants, and there were all sorts of real and imagined plots. There are stories of a foiled plot by the IRA to knock off Prince Phillip, on a solo visit in 1973, in revenge for the British army having shot 14 unarmed Catholics. It was quickly hushed up.

Debates also raged with each Royal visit about the huge cost, and to some the unseemly abasement before a Monarchy from so far away. The Premier of Tasmania, Robert Cosgrove and the councillors of Katoomba in separate ways, kept their distance from the festivities and official occasions.

The book is in itself not political or anti the Monarchy. The undercurrent throughout is the importance – to this day – of the Royal Family to Australia despite the constant melodrama of their lives (just like ours). They have been more than show ponies, or rich, famous people in a fairy tale that glued us all together. They are revered, and most of the time they behaved with regal aplomb, at least while in public.

And importantly, during times of rapid changes in Australia after the war they were a continuing, stabilising force – with some power though still as shocked as many when in 1975 when the Queen’s man in Australia, Governor General Kerr, dismissed the democratically elected Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam.

The Queen was eventually forgiven and in her l977 tour, the entire parade of dignitaries, and panoply of plenty were on display again. Jane Connors writes of a rather startling table centrepiece at a Parliamentary Reception, made of marzipan Rosellas.

A terrible incident in the British Empire

Jane Connors has retraced in lively detail all the Royal visits starting with Prince Alfred in l867 who had to deal with a public tour of “overwhelming scale of intensity and pomposity.” As Jane Connors writes, the hapless Prince was at the time cruelly described by historian Manning Clark as a young man hoping rather to “whore and hunt” his way around the country.

He was instead constantly caught up in parties and parades, official visits, and dinners. There was a tragedy; at a grand fireworks display in Bendigo three little boys burned to death.

Against a backdrop of seething Catholic and Protestant hatreds the Prince himself later came close to death on Clontarf Beach during a fund raising event. He was shot at close range by a deranged Irishman. Only the thick quality of his royal braces saved the Princes life. It was a dreadful event forAustralia and British diplomacy in the UK. The world was aghast.

Prince Alfred himself forgave Australia. In return, grateful Australians donated money to build the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney. The would-be assassin, a Mr O’Farrell, was hanged at Darlinghurst Gaol, now the National Art School.

After WW2, Australia began to do well. The economy began to boom with the influx of immigrants and refugees, industrialisation, import restrictions, sheep and wheat. Australia became rich, and it was an outpost of Mother England. It was conformist, conservative, and mothers worried about their daughters going out with ”wogs”. The Protestants still looked down on the Catholics. A few Irish were collecting money to send back to the IRA in the UK. But on the whole, Australia was beginning to live the good life, buoyed by immigration, and able to buy things like refrigerators, phones, even cars. London remained the centre of the world.

Royalty from Elsewhere

There were also Royal visits from the Pacific, the Middle East, and Asia: Queen Salote and other Tongan Royals, King Bhumibol and Queen Sirikit of Thailand, and the Shah of Iran and his beautiful wife, Soraya who left Sydney high society “humbled”, among others.

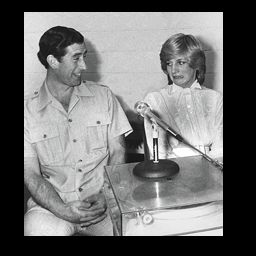

There were, of course, many other royal visits, right up until that of Prince Charles and Diana gave the Monarchy a whole new chapter, such as one might have seen in Downton Abbey a few steps up some sort of class ladder. There was gossip about fights between Charles and Diana over her stealing the limelight.

There were, of course, many other royal visits, right up until that of Prince Charles and Diana gave the Monarchy a whole new chapter, such as one might have seen in Downton Abbey a few steps up some sort of class ladder. There was gossip about fights between Charles and Diana over her stealing the limelight.

Most recently Crown Prince Frederik of Denmark and his Crown Princess Mary, Australia’s own delightful and lovely Tasmanian visited us.

This is a splendid book of deep scholarship, with fine unpretentious writing, humour and insight. It tells the story of cultural changes, and doesn’t ignore the undercurrents of our emerging identity with new ideas, wider perspectives and globalisation, always through the prism of our relationship with the Monarchy.

I do hope Queen Elizabeth has kept a personal diary all these years. If it is ever released, it will be delicious to read. Her Majesty has a sense of humour and I wonder if she will mention the Guard of Honour of the rams rumps in Wagga Wagga.

KM.

Jane Connors is an historian and senior manager with ABC Radio.

“Royal Visits to Australia” is available from the National Library $39.95.

Also from booktopia.com.au and selected bookshops.